By Emily Rees[1]

Introduction

In my previous blog, I highlighted the enigmatic life and career of the Victorian naval engineer Henrietta Vansittart (1833-1883), who I had been researching as part of the Electrifying Women project on the history of women in engineering. I found myself intrigued by this self-trained engineer, who had been introduced to engineering through her father James Lowe, and who held patents for the Lowe Vansittart propeller in both the UK and the USA.

There are not that many examples of women who practised as engineers and held patents in the 19th century, though they did exist, for example, Hertha Ayrton and Sarah Guppy. Henrietta Vansittart, despite belonging to this list, appears to have received little academic attention, suggested reasons for which I discussed in the previous blog. I also examined the veracity of the various blog posts that exist online, finding some of them to contain false or unverifiable information in them.

I concluded that further research was needed into her life and work; not only did Vansittart lead an exceptional working life, she also had a colourful – and ultimately tragic – personal life.

Since writing previously, I have sought to find primary materials that might help bring more to light and was able to trace material about Vansittart in three different archives:

A pamphlet written by Henrietta Vansittart about the Lowe Vansittart propeller, a copy of which is held in the Science Museum Group library; letters from Henrietta Vansittart to Edward Bulwer-Lytton in the Bulwer-Lytton archives, held by Hertfordshire County Council Archives; and Henrietta Vansittart’s case notes from St Nicholas Hospital, held in The Tyne & Wear Archives.

Through the pamphlet, letters and case notes more depth can be given to what was already known about Vansittart, providing greater insight into her personal and professional voice, her personality, and the manner of her death.

The Pamphlet

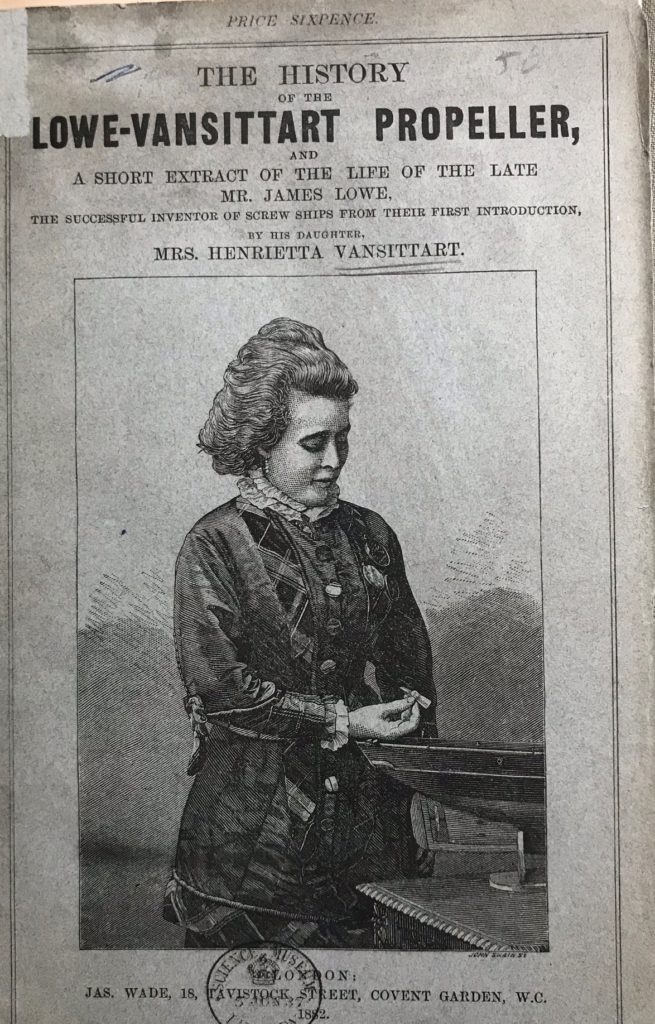

It is fairly easy to discover that Henrietta Vansittart had a publication entitled The History of the Lowe Vansittart Propeller and a short extract of the life of the late Mr James Lowe, the successful inventor of screw ships from their first introduction (there’s a listing of the item on Google Books) but it isn’t held widely in libraries across the UK.

With the assistance of my Electrifying Women project colleague Dr Elizabeth Bruton (Curator of Technology and Engineering at the Science Museum), we found a copy in the Science Museum Group library, which we were able to view. We knew already that there was a model of the Lowe Vansittart propeller held in the Science Museum Group collections.

This small book, published in 1882 (one year before her death), was published by Jas Wade in London and sold for 6 pence. The pamphlet (with a newspaper article inserted into it) was gifted to the Science Museum by RB Prosser. This is probably Richard Bissell Prosser (25 August 1838 – 18 March 1918), a patent examiner and a biographical writer.[2]

Ostensibly, one of the aims of the pamphlet is to celebrate the work of her late father, showing her persistent dedication to him after his death in 1866. This is apparent in the aforementioned newspaper cutting, pasted into the inside front cover from The Daily Graphic on Saturday 11 November 1905, which records the dedication to James Lowe on his tomb in Ewell churchyard:[3]

Sacred to the memory of James Lowe, Esq., who was born May 13th 1798 and met his death from an accident the 12th October 1866. He was the Inventor of the Segment of the Screw Propeller in use since 1838 and his life though unobtrusive was not without great benefit to his country. He suffered many troubles but bore them lightly as his hope was not of this world but in our Saviour. Erected by his sorrowing Widow and his affectionate daughter, Henrietta Vansittart.

Vansittart’s inclusion by name as the last word on his tombstone, which she erected, shows the importance she placed on their relationship (and emphasising her place in it for all to see). Working on, and promoting, his screw propeller was clearly more than just engineering, it was about family legacy.

For the purposes of learning more about Henrietta Vansittart, crucially the frontispiece shows a rare portrait of her examining a scale model of a ship with the associated scale model of the Lowe-Vansittart propeller in her right hand (see image above). I can now be certain that this image, which had appeared in other sources, can be rightly attributed as a portrait of her.

The pamphlet, which contains technical descriptions of the screw propeller, demonstrates Vansittart’s writing ability and technical knowledge. The pamphlet also verifies that she delivered the contents as a lecture to the Association of Foremen Engineers and Draughtsmen on the 1 April 1876, which was entitled “The Screw Propeller of 1838, and subsequent improvements”.

She also provides reference to a later (seemingly ad hoc and informal) presentation before the London Association of Foremen Engineers and Draughtsmen on “Screw Propellers versus Paddle-Wheels as a means of propulsion, for river traffic” presented on 4 September 1880 and Vansittart’s reply to the same on 1 November 1880.

We learn more, therefore, about her public life as an engineer, who both spoke (more than once) publicly about her work and published on it.

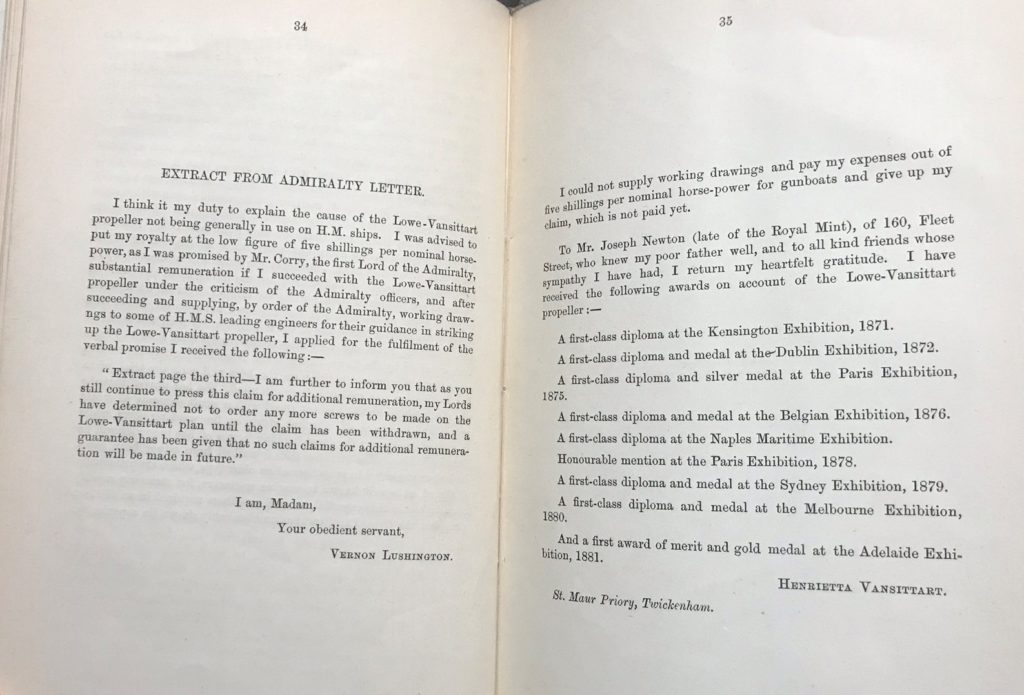

Furthermore, the pamphlet includes printed correspondence between Vansittart and the Admiralty, the government department responsible for the command of the Royal Navy. The undated extract from a letter from Vernon Lushington explain why the Lowe Vansittart propeller was not being used on Royal Navy ships. Vansittart’s printed reply lists the various awards won by the propeller including a first-class diploma at the Kensington Exhibition in 1871, among eight other international awards (see image below).

We see from this the pride she took in the propeller and her desire to defend it to its detractors. The pamphlet also contains an extract from The Times, 24 December 1869, detailing the successes of a trial of the propeller, which is emphasised throughout.

While the pamphlet (and the previous paper read aloud) are undoubtedly written by Vansittart, she presents her defence as on behalf of her father’s work. As is often the case for women in this period, she chooses to present her voice and expertise as a service to the work of a man, rather than claiming it in her own right.

Nonetheless, her authority about propulsion methods is clear in the pamphlet, as is her dedication to her father and continuing his work (without claiming that it was, indeed, her eventual success rather than his).

Letters to Edward Bulwer-Lytton

From my initial research into Henrietta Vansittart it quickly became apparent that she was interesting not only because of her atypical position as a female engineer, but also because of her unconventional personal life. According to the blogs I read, it appeared to be commonly known that she had a long-lasting affair with Edward Bulwer-Lytton, though it was not clear to me where the evidence for this came from.[4]

Through searching the National Archives online catalogues, I discovered that some of her letters to Edward Bulwer-Lytton were held at the Hertfordshire County Council archives. To be exact, they hold 17 letters from Henrietta Vansittart, 16 of which are to Edward Bulwer-Lytton (dated 1862-1872) and one of which is to his son, after the death of Edward Bulwer-Lytton in 1873.

Having read the letters, they offer indisputable proof that the two were intimately connected for many years and that they were in correspondence until Bulwer Lytton’s death in 1873.

The pamphlet offered us a version of Vansittart as faithful daughter and technically literate engineer, capable of speaking before a formal association and defending her work to the Admiralty. The letters uncover her personal voice, her voice as a lover and a friend.

The tone of the letters is often passionate, and it is obvious from them that their affair was tumultuous, long-lived and mutually felt. Some of the early letters are almost impossible to decipher, perhaps deliberately to obscure what is being said. There are examples of misunderstandings, reconciliations and mysterious visitors bringing slanderous letters to Vansittart about another affair he was allegedly having at the same time.

One letter from December 1862 begins:

Dear Sir Edward,

I cannot bear the suspense of waiting for an answer from you, it is killing me, and I also think I shall die for your letter has given me such a shock that I feel myself gradually sinking under it […]

Nine years later, on the 5 June 1871 she wrote:

You are cruel to answer my letter as if its contents contained mercenary feelings; and you need not speak to me about my husband as I do not care a bit about him, neither do I care a jot about money. I did not estrange myself from you; you estranged yourself from me but will go away as I said that I have finished three of four little things which I have to do and no one shall be able to find me.

In addition to the enigmatic line about disappearing, this letter offers some insight into how their affair ended (though there is correspondence after this point). It also indicates that she did receive an allowance from Bulwer-Lytton and presumably this might link to the money he left in his will to her and her husband, Frederick Vansittart. There is some evidence in other letters that he paid for her upkeep, while she was estranged from her husband.

There is one letter (undated) in which she discusses her engineering work. She refers to criticism of her father’s designs by the Admiralty, which she firmly refutes, thus there are links between the pamphlets and these letters about her wish for her father’s work to be properly respected.

The final letter is to Bulwer-Lytton’s son offering condolences for his father’s death. Some kind of misunderstanding had occurred; she offers her apologies for causing any offence, stating she never meant to imply she wanted to attend his father’s funeral. She goes on to list the esteem in which her family held his father.

It would of course have been a huge impropriety for her to attend the funeral, yet it was still moving to read this letter, knowing that she was unable to pay her respects to someone who had evidently played such a large role in her life for many years.

Case notes

Another widely reported fact about Henrietta Vansittart’s life was that she died in an asylum in Newcastle from anthrax and acute mania in 1883, after being found wandering the streets in a manic state. A colleague at the University of Leeds, Dr Katherine Rawlings, who works on women inmates at asylums in this period, helped me to track down Vansittart’s case notes in the Tyne and Wear archives.

The handwritten case notes state that she is a 42-year-old woman (she was born in 1833 so this is an incorrect age), who has been admitted to the hospital on the 19 September 1882 with her first attack of mania that has so far lasted 8 days.

The notes state that she is a danger to others and prone to violence. According to the notes, she shouted loudly about ‘the devil, the Virgin and God.’ On admittance, her body was marked with bruises and she spoke of personal interviews with ‘the Virgin.’ Throughout her stay, the case notes indicate that she was often violent and prone to excitement, talking frequently on the same religious themes.

Her death is listed as taking place on the 8th February 1883, ‘during last night she gradually sank. Stimulants were given but she died this morning at 7.45, in the presence of nurse [first name illegible] Ross, of acute mania and anthrax.’

The painful effects of the anthrax, including weeping boils, are described in the case notes, and had worsened before she died, but there is little detail in the notes about how it began and its nature.

In her letters to Bulwer-Lytton, her persistent ill health was mentioned, though nothing relating to mental illness or anthrax. In a letter from 1870 she explains that her doctor recommended she did not take a trip to the USA that she had been planning (this trip may have been to promote her patent in the USA which is dated May 4, 1869).

For the most part, we learn little from the case notes about Vansittart’s life, only find more confirmation that her life ended in a distressing way, only in the company of a nurse.

Conclusion

In starting to research Henrietta Vansittart, I found glimpses of insight into the life of an unusual woman, defying expectations about the place and lives of Victorian women. I found a series of blogs that gave details about her life, but little evidence to support the claims.

In fact, the general arc of her life has been reported correctly. The primary material I have found adds detail and texture to the skeleton of her life that we already know. From it, we can surmise that her relationship with engineering was deeply personal, stemming from a desire to continue her father’s work and protect his legacy.

Nonetheless, despite this personal motivation, her pamphlet reveals her technical ability and deep understanding of the engineering involved in propulsion methods. It is evident that the success of the Lowe Vansittart propeller rested on her ingenuity. We see that she took pride in her work and was able to present on it to all-male audiences, competently defending it when she felt it necessary.

The passion she had for her work is evident in her personal life too. The precise and technical writing of the pamphlet is replaced with dramatic, heartfelt prose in her letters to her lover Edward Bulwer-Lytton, who was clearly an influential figure in her life for many years.

In her final months, at only 42 years old, her vigour is expressed only in her distressed state, deemed a danger to herself and to others, dying an untimely death. Henrietta Vansittart, it would seem, did a lot of living before then, achieving some extraordinary things, propelled by her singular vision.

Archive Material

Henrietta Vansittart, The History of the Lowe Vansittart Propeller and a short extract of the life of the late Mr James Lowe, the successful inventor of screw ships from their first introduction (London: Jas Wade, 1882).

N.B. a copy of this can also be found in the University of Bristol library and may also be found in other depositories.

Bulwer-Lytton archives: letters from Henrietta Vansittart, reference numbers: DE/K C25/136 and DE/K C37/95.

Casebook from St Nicholas Hospital, Gosforth, reference number: HO.SN/13/31 – 24 April 1879 – 18 October 1886.

For more information about how to conduct your own archival research on women in engineering, you can use the project’s research guide, found here, and the general resources pages.

[1] I’d like to thank my Electrifying Women project colleague Dr Elizabeth Bruton for her help with this blog post: her assistance with locating and viewing archival material and for her insightful comments on this blog, in addition to her shared interest in the life and work of Henrietta Vansittart.

[2] Dr Bruton raises the pertinent question of why Prosser was interested in the pamphlet, was it for the patent or for biographical reasons? More research is required here to follow that lead.

[3] According to the Epsom and Ewell History Explorer blog post on the family, the tomb can still be found in the graveyard but the inscription is now almost completely eroded. The inclusion of the cutting raises other questions about who put it there (was it Prosser?) and why this particular story was running in 1905 in the newspaper.

[4] One blog indicated that, in 1860, Disraeli commented that Bulwer-Lytton’s affair with Vansittart was causing Bulwer-Lytton to be absent from the House of Commons, but I have not yet been able to verify the source for this claim.