Guest post by Nina Baker

From the 1920s to the middle of the 20th century in the United Kingdom (UK) there was a blooming culture of organisations of women working to support every aspect of their working, domestic or leisure lives. It was also the era when how we heated our homes, washed our clothes and cooked our food radically changed for nearly everyone.

This blogpost looks at the activities of three women’s organisations, with thousands of members across the UK, that were devoted entirely to guiding the housewives and the industries involved in producing and selling the three main energy forms: electricity, gas and coal.

In the vast majority of homes, even those with mains gas and electricity, the first task each morning would be for a woman to clear out and relight a coal fire of some sort. That woman might be the housewife or it might be a servant in the earlier part of the century, but it was dirty, tedious, essential, daily work done almost entirely by women.

Until the arrival of nuclear power in 1956 and natural gas from the North Sea became commonplace in the 1970s, the vast majority of 20th century energy needs in the UK were either directly or indirectly derived from coal. The government standard for the homes being planned for post-World War Two reconstruction was based on a background ‘warmth’ of only 10 degrees centigrade, augmented in living rooms by an open coal fires or stoves, individual electric fires or gas fires in the former fireplaces. Many homes also used very dangerous portable paraffin stoves and most homes would not have any form of central heating until the 1970s.

Electric Women

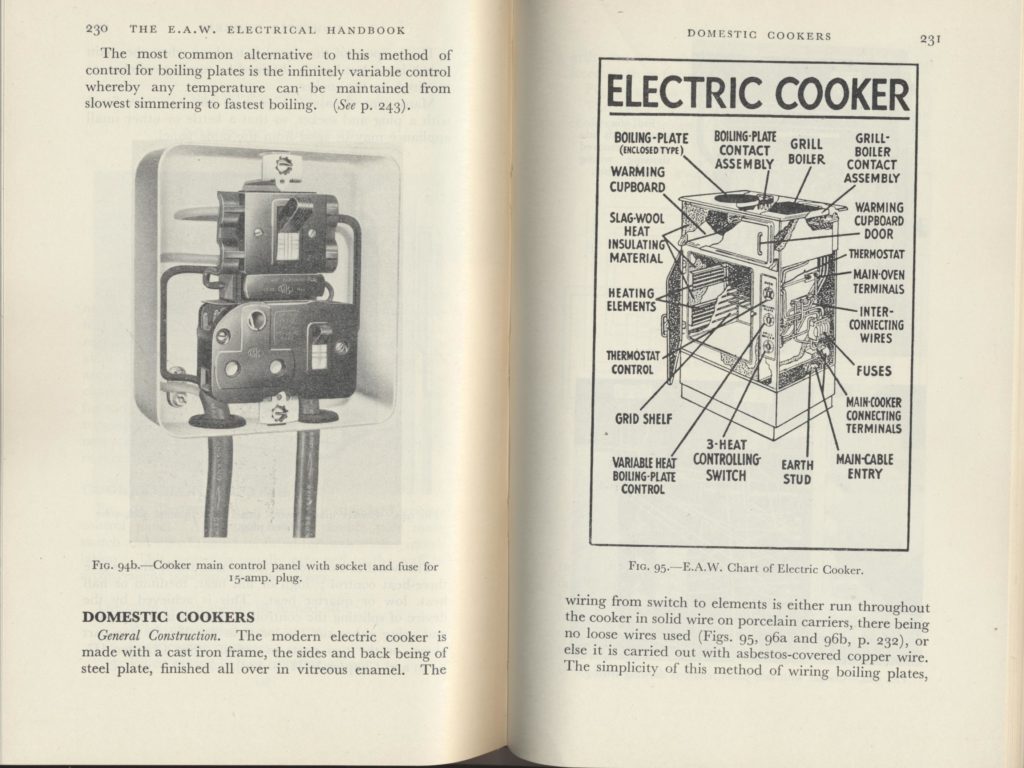

When electrical power started to be more widely supplied to ordinary households it was mainly for lighting but women with technical backgrounds could see how electrical household appliances such as cookers, irons and washing machines could massively reduce the physical drudgery of women’s housework. They set up the hugely successful and very well-known Electrical Association for Women (EAW) in 1924, its success driven by the energy of Caroline Haslett.

Until the EAW finally closed in 1986, there were branches all over the UK, providing basic electrical education classes for housewives, advice to government and industry and training for those who demonstrated appliances in showrooms or taught domestic science in schools. The EAW’s handbook went into multiple editions and their work continued to be high profile right through the 1940s, 50s, and 60s, only petering out as electrical household equipment became ubiquitous.

What is far less well-known is that there were two other organisations doing more or less the same thing on behalf of gas and solid fuels: the Women’s Gas Council and the Women’s Advisory Council on Solid Fuel.

Gas Women

The Women’s Gas Council (WGC) was set up in 1935, driven by its first organising secretary, Katherine Halpin, previously the Foreign Secretary’s personal secretary. The first president was Lady Edith Londonderry, with chairman Mrs Wolsley-Lewis. Halpin’s personal energy was the essential factor in establishing new branches nationwide, and within a year the new organisation had 7,000 paid-up members and double that by 1939.

Meetings were generally held in the local gas showroom where the local gas board’s ‘home service women demonstrators’ could oversee talks on domestic topics, by no means all talks being directly related to gas use. There was clearly a strong demand from housewives for social groups with a purpose, but the WGC was also a way to collect and distribute information about gas as it affected the home, child welfare, hygiene, housing, slum clearance, and smoke abatement – all subjects of vital importance to women. Certificated Gas Housecraft courses were run for housewives and women gas showroom demonstrators.

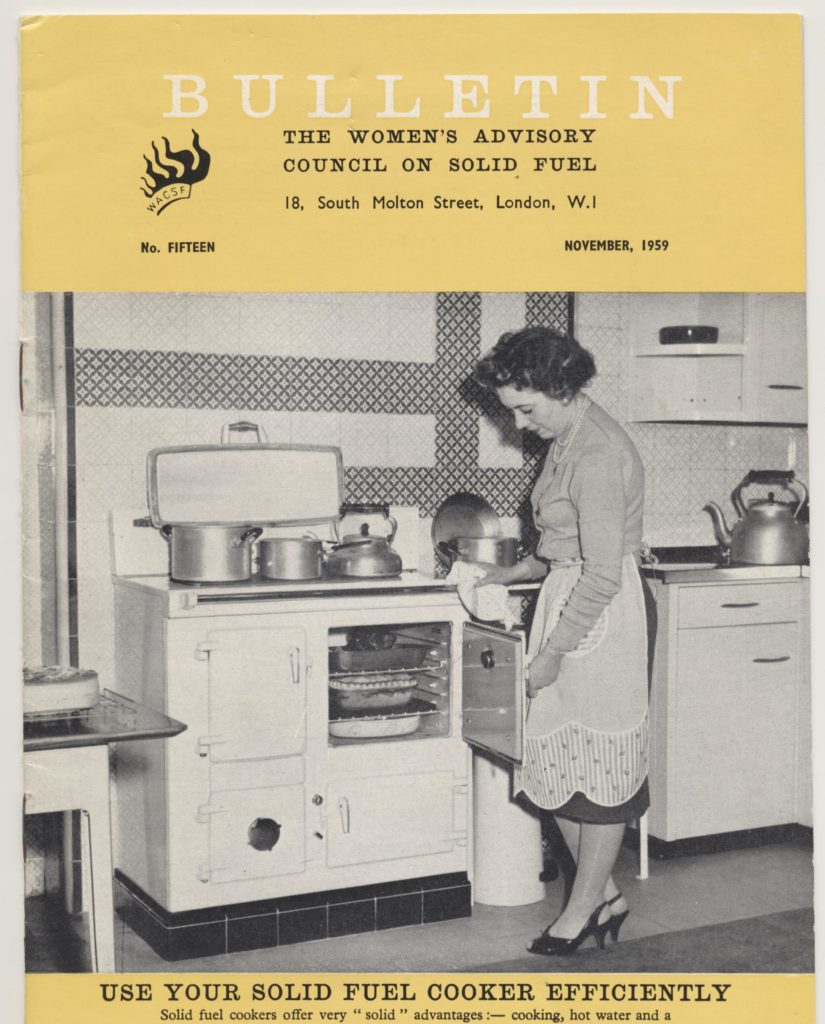

The WGC published a handbook, Handywoman’s Course. Maintenance of light, heat and water supplies. Gas appliances, in 1942 and, in 1966, Gas and its Domestic Uses: A Handbook for Students of Home Economics. WGC’s magazine for members, Fanfare, seems to have lasted from 1936-1947 before its renaming as Commentary in 1948, but the WGC also published numerous leaflets under the umbrella title of “I Pass This On To You” with recipes and household management tips.

In 1953 the WGC became the Women’s Gas Federation and Young Homemakers and continued until about 1973. The only major work about the WGC is the late Anne Clendinning’s book, Demons of Domesticity: Women and the English Gas Industry, 1889–1939, based on her PhD thesis.

There was also a similar organisation in Australia, the Women’s Gas Association, founded in 1955, under the presidency of a Mrs Andrews, wife of a prominent industrial gas engineer. The WGA was very popular even in the 1960s, with branches often having waiting lists. As with their UK sisters, such women’s organisations put on talks and entertainment for members and did local charitable good works.

The ‘Solid’ Women

The Women’s Advisory Council on Solid Fuels (WACSF) emerged from the plethora of women’s organisations that sprang up around the beginning of the Second World War. The Women’s Group on Public Welfare was the umbrella organisation for representatives from each of the organisations.

It formed a number of sub-committees on a wide range of topics from evacuation to food education and including such technical topics as planning, air raid shelter design and fuel economy, records for which can be found here. The latter sub-committee became the WACSF in 1943 under the chairmanship of Lady Ruth Egerton (1884-1978) whose husband was the chief scientific advisor to the Ministry of Fuel.

WACSF is far less well-known than either of its two older sister organisations, despite the prevalence of coal heating in the home and the fact that coal was the source of both gas and electrical power at the time. Almost nothing is written about it, and any archival materials, for example, at The Women’s Library at the London School of Economics, are currently out of reach due to Covid-19 constraints.

There seem not to have been local WACSF branches with members, in the way that the EAW and WGC had, but certainly it employed paid lecturers to tour the country giving talks to other women’s organisations and domestic science teacher training colleges.

In 1950 the Council itself consisted of 9 officers (including paid staff), 31 represented organisations, 8 individual members and 7 observers. Financially the organisation depended upon significant but unconditional grants from the coal mining and distribution bodies. WACSF officers reciprocally represented it on other bodies in the energy field, and were somewhat unkindly nicknamed “The Solid Women”.

In a 1951 answer to a parliamentary question the then Minister of Fuel and Power, Mr P. Noel-Baker said of the WACSF:

I am aware of the excellent work done by the Women’s Advisory Council on Solid Fuel to further the intelligent use of solid fuel in the domestic field. This comprises education, information, and service to the general public by means of training courses, conferences, exhibitions, demonstrations and publications on the efficient use of solid fuel. The technical advice of my regional fuel engineers is always available to the Council’s regional organisers and every encouragement is given by my Ministry to their work.

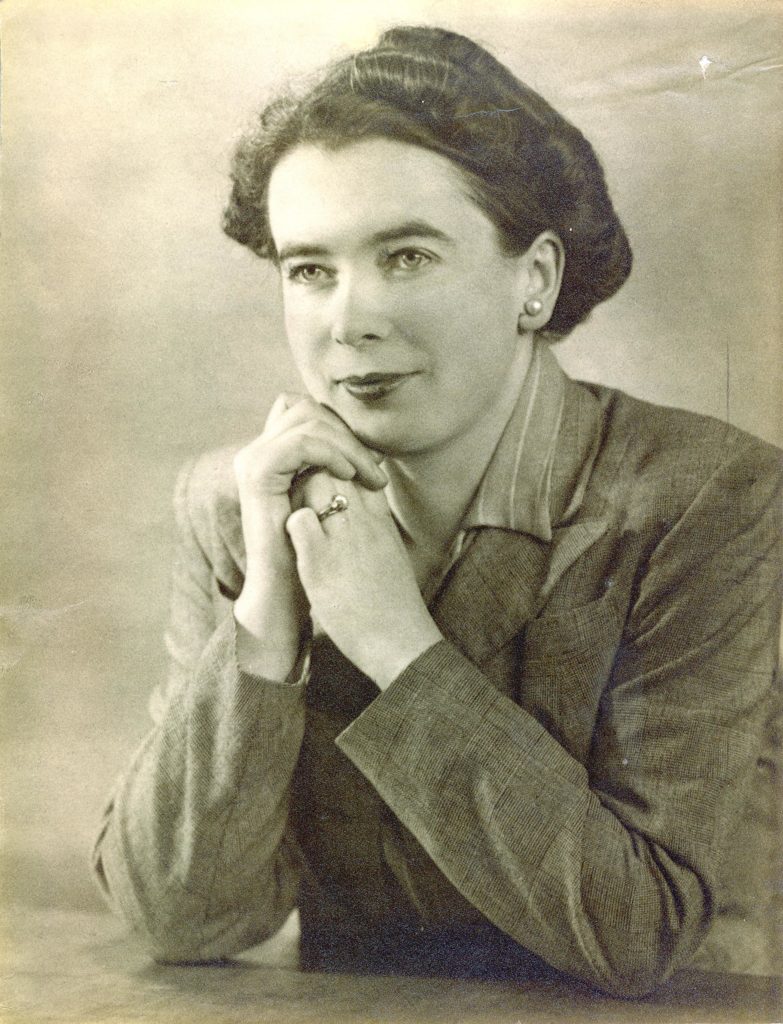

Its General Secretary at start-up in 1943 was Elspet Fraser-Stephen (nee Mackenzie) MA, Associate of the Institute of Fuel (1908-1965), who was also the author of most of its publications up to perhaps the mid-1950s (she is pictured above). As with the EAW and WGC, the WACSF produced a handbook for domestic science teachers and their trainers – Solid Fuel Housecraft (1950).

It may be indicative of coal’s downward popularity trajectory that even in 1950 the book had to acknowledge that increasingly homes with solid fuel heating or cooking might also have a gas or electric cooker. Whilst emphasising that teachers should promote the newer more efficient models of coal-fired boilers, heating systems and cookers, even these look clunky and dated to modern eyes.

Unlike the handbooks of the EAW and WGC, which get well into the basic science and principles of their energy sources, the WACSF book only covers the construction of the various appliances and explicitly says it would not expect girls to have any interest in coal mining.

Fraser-Stephen was succeeded as Secretary by WACSF’s technical officer, Mary Leigh, in about 1953, and later by Kathleen Victoria Bradbury, who wrote reports for WACSF from the early 1960s but about whom otherwise not much is known.

In parallel there were women scientific civil servants in the various government research establishments (and industrial laboratories) connected with energy matters doing work on more efficient heating and cooking sources, smokeless fuels, reduction of air pollution and similar topics.

Leadership and Networks

The women involved in these organisations always seem to have included an aristocratic president or chairman (none of them were ever called chairwomen), and committees made up of other well-connected women whose names seem also to crop up in other women’s groups of that time.

These women sat on each others’ committees and advisory groups and, whilst many of them were well-qualified professionals in their fields, there was also a scattering of women whose lives were that of the “engineer-by-marriage”. This phrase coined by Lady Margaret Moir about herself, was true of many intelligent women who made it their business to pay attention to their husbands’ work and build up their own expertise in that field.

There was also a strong sense of ‘noblesse oblige’ – that high social status should be reflected in public service. Many of these women also sat on or advised government committees and advisory groups, frequently being the only women present in what remained very much a male environment.

However, the households for which all this work was notionally being done were probably of a very different social class. Bearing in mind that even many middle-class homes outside the cities and bigger towns did not even have electrical power supply until after World War Two, the chances of working class families making any change to their fuel use for cooking and heating were slim.

Working class social housing, especially in the coal-producing areas, would have had solid fuel cookers, heating and hot water systems and the householders would not have had any choice even if they could have afforded to change. Slightly more prosperous households might have all three modes: electric light, a gas cooker and coal heating. Even today, all-electric homes are rare.

The tone of the advice, whilst clearly aiming to be woman-to-woman had perforce to take account of the affordability of what was on offer. Whilst the EAW’s handbooks and showrooms were aiming for an ideal future/futuristic home and a modern-thinking housewife in it, that had to be a middle class or better until well into the post-war period.

In marked contrast, the solid fuel handbook makes frequent references to schools being equipped with out of date equipment both for their own use and for the teaching of housecraft. The impression is that the Solid Women knew they were fighting a losing battle but wanted to help ‘their’ housewives as best they could.

How all of this was received by the target audiences of schoolgirl housecraft pupils or housewives would be worth knowing more about for each of the three fuels. Whilst the EAW is well represented in archives and research, perhaps due to it association with the Women’s Engineering Society and its forward-looking offer, the WGC and WACSF are scarcely known of today and could definitely benefit from some more systematic research.

About the author

Dr Nina Baker is an independent engineering historian specialising in construction history and the history of women who worked in engineering. You can read more about Nina’s research on her blog on women in engineering.