By Emily Rees

In 1964, a report on women’s current place in science and engineering across the globe, stated it knew of no women engineers in the whole continent of Africa.[1] Yet, a year later, a young female engineer from Uganda – Miriam Muwanga – joined the UK’s Women’s Engineering Society (WES) as a graduate member. Perhaps the report had not gleaned the whole picture.[2]

After that first mention in 1965, Miriam appears a number of times in WES’ journal The Woman Engineer, until her obituary in 1975, which stated that ‘Uganda has lost its first woman engineer and all who knew her have a real sense of personal sorrow.‘[3]

Yet to search for her name now – other than these several references in The Woman Engineer – yields no results.[4] Why has one of the candidates for Uganda’s first woman engineer been forgotten?

The most straightforward answer might be the nature of her death – in 1975 Miriam died tragically young, after being involved in a car accident in Kampala, Uganda.[5] Her birthdate is – as yet – unknown, but the dates of her education, and the fact she was recently married with a baby daughter at the time of her death, suggests she might have been in her early thirties.

Miriam, it would appear, is an example of an engineering career, and life, cut short by tragic circumstances, as her obituary in The Woman Engineer testified:

Miriam was charming, gifted, had great dignity and was excellent company. She was lovable and loving. Her death is a dreadful tragedy, an appalling waste of a wonderful, brilliant young life.[6]

From what the information in The Woman Engineer tells us, Miriam achieved a lot of things in a short space of time, working and studying in both the UK and Uganda. This blog post seeks to remember her remarkable achievements.

The name Miriam Muwanga (after marriage, Sebaggala) first appears in The Woman Engineer in 1965. It reports that a Miss M. Muwanga from Uganda was a special trainee at Associated Electronics Industries (later Metropolitan Vickers) and studying for an HNC at John Dalton College of Technology in Manchester (now Manchester Metropolitan University).[7]

Miriam would not necessarily have been completely alone as a young woman travelling from Africa to study at a higher education institution in the UK. In the second half of the twentieth century, we have found evidence of women coming from countries in Africa and Asia to study STEM subjects in the UK. Earlier examples, from the 1940s, include Ghanaian zoologist Leticia Obeng, who studied at the University of Birmingham, and Chinese civil engineer Ying Hsi Yuan, who studied at Liverpool University.

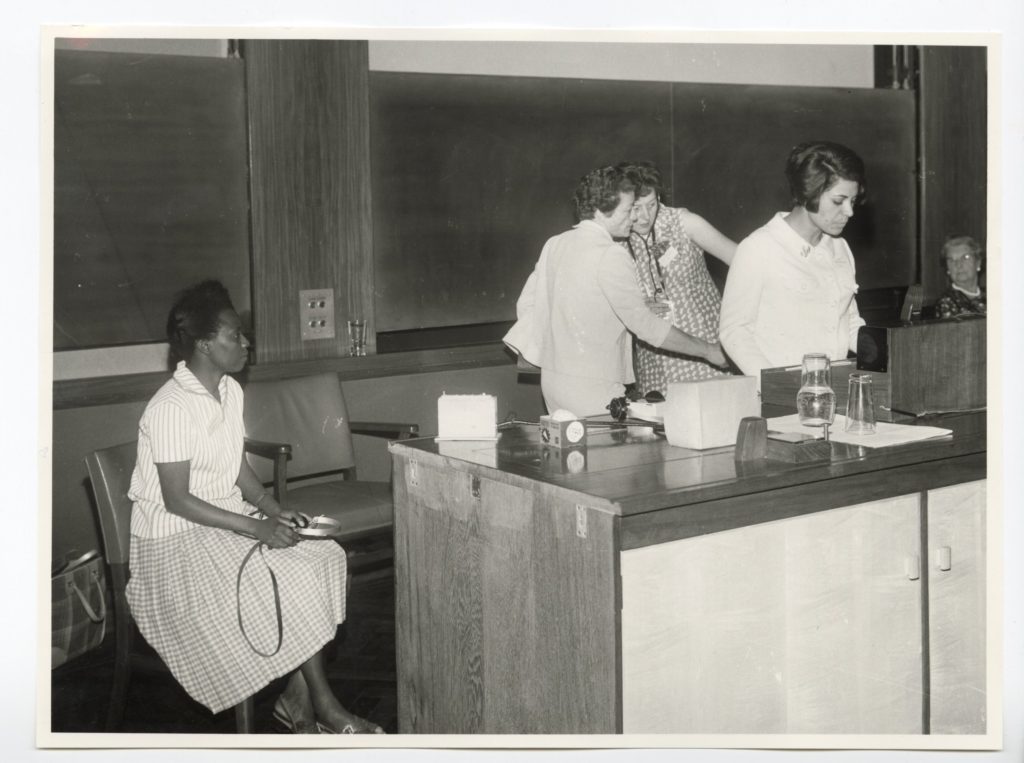

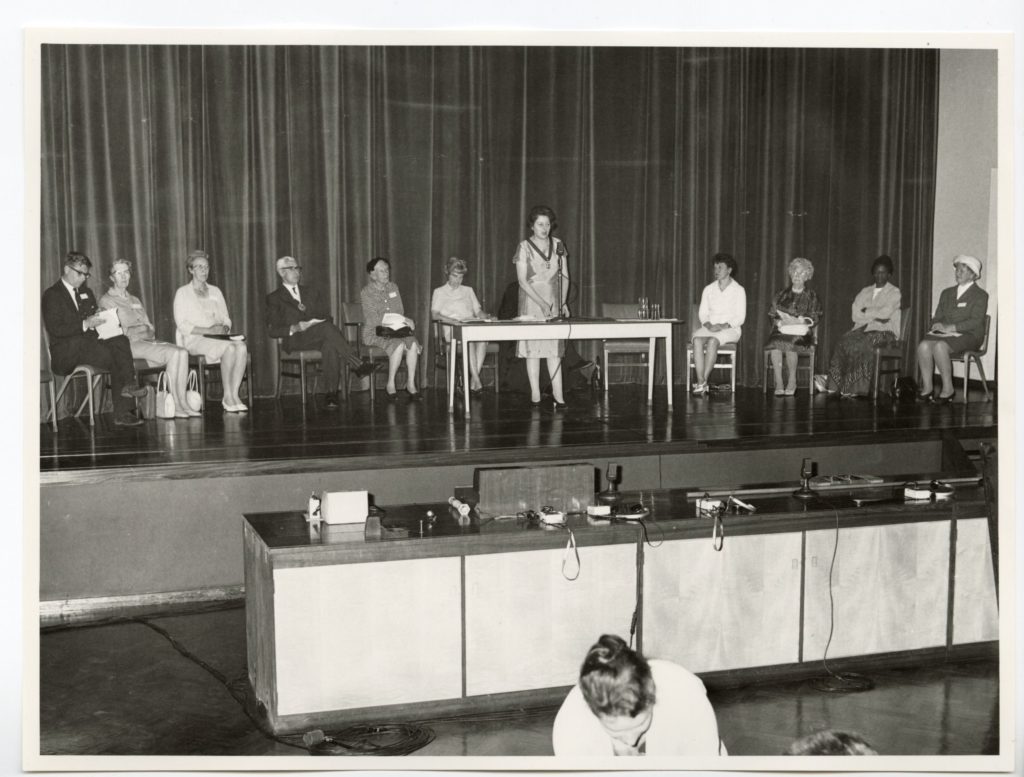

Beyond the university setting, the formation of the International Conference of Women Engineers and Scientists (ICWES) in 1964, led by the Society of Women Engineers in the USA, points to other ways that a growing international conversation was taking place between women engineers and scientists, something which Miriam also partook in. In 1967, she was awarded funding by the Caroline Haslett Memorial Trust to attend the second ICWES meeting, that took place in Cambridge, England, hosted by WES (see first two images).[8]

Her marriage was announced in the Autumn edition of The Woman Engineer in 1968, which might be the reason she returns to Uganda around this time, or it might have been her desire to help her country and her people, which is spoken of in her obituary.

In 1969 she wrote an article for The Woman Engineer called ‘Focus your Eyes on Uganda’ where she speaks of some of the challenges the country faced, in the wake of decolonization and mounting political tension. She writes about the potential of women to help strengthen the country’s prospects:

While men are struggling for power [women] are organising themselves into clubs, associations and societies. When women gather they do not talk about the wars in various parts of the world or the deceitfulness of world politicians; they discuss educational problems, family planning, home economics; they learn new crafts, and improved methods of looking after the family.[9]

On this basis, Miriam writes that she was inspired to form The Women’s Technical Society of Uganda, a place where women could discuss their careers, go on visits, and take their experience to schools.

The following year, she sends more news from Uganda, where she by then worked as the design assistant at the Uganda Electricity Board, also in charge of the Drawing Office and Library. In the same year she became an associate member of WES. The article quotes letters from Miriam where she talks of the activities of The Women’s Technical Society of Uganda and the setting up of an Institution of Engineering Technicians for both men and women, for which she was elected financial secretary.[10]

We learn that in 1970 she returned to the UK to continue studying,[11] serving as a committee member for WES in 1971.[12] In 1972, she was recalled to Uganda by the Ugandan Electricity Board.[13] She became the editor of their journal in 1974,[14] the same year her daughter, Kulabata, is born[15] and this is the final entry before her death is announced in 1975.

There are lots of aspects of Miriam’s career that can be researched further, and many questions can be raised. Questions such as: how did she come to study in the UK in the first place? What was her prior training and education in Uganda? Was she exceptional in Uganda at the time or did she have other fellow female students? What happened to the The Women’s Technical Society of Uganda?

With limitations on travel and access to archives due to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, digitised sources like The Woman Engineer have been invaluable for research, but in the case of an engineer like Miriam Sebaggala, it has led to obtaining information from a lopsided angle. Without accessing material from her home country, there is a reliance on sources from the UK, namely the WES archives, when clearly a chance to explore available archives in Uganda could offer a whole new perspective on her work and life.

While recognising the limitations of the current, necessity-based methods, it is apparent that Miriam, through WES, and her education, built a meaningful connection with the UK, which led to her featuring often in The Woman Engineer. The next phase of research will need to turn to sources and archives in Uganda.

Finding out more about The Women’s Technical Society of Uganda has so far proven fruitless, but interestingly, living engineer Proscovia Margaret Nguki, who is credited as the first Ugandan woman to study engineering, is cited on Wikipedia as one of the founder-members of the Association of Women Engineers, Technicians and Scientists in Uganda (in 1989). This is an organisation the Electrifying Woman project is keen to know more about, including whether it has any origins in The Women’s Technical Society.

There are further connections to follow up: Proscovia Nguki serves as the chairperson of the board of directors of Uganda Electricity Generation Company Limited (UEGCL), a successor of the Ugandan Electricity Board, for which Miriam was an employee. Do the UEGCL hold any archives? And do these organisations and the people who worked for for them have any memories of Miriam? Evidently much more research is needed.

In remembering the life of Miriam Sebaggala, potentially Uganda’s first female engineer, and certainly a dedicated champion of women, we can recognise the way our histories are only partial, as it is so easy for women, and their achievements, to disappear.

[1] This report was presented at the first International Conference of Women Engineers and Scientists (ICWES) held in New York, USA in 1964.

[2] The Woman Engineer (Winter 1965 9:19, p. 18). N.B. The Woman Engineer is the journal of the UK’s Women’s Engineering Society, since 1919, and digital copies can be found here.

[3] The Woman Engineer (Summer 1975 11:16, p. 4).

[4] Search results may, of course, vary across countries. These searches were conducted from UK/Switzerland.

[5] According to her obituary in The Woman Engineer (Summer 1975 11:16, p. 4).

[6] The Woman Engineer (Summer 1975 11:16, p. 4)

[7] The Woman Engineer (Winter 1965 9:19, p. 18).

[8] The Woman Engineer (Spring 1967 10:4, p. 18)

[9] Miriam Sebaggala (nee Muwanga), ‘Focus Your Eyes on Uganda’, The Woman Engineer (Spring 1969 10:12, p. 15).

[10] ‘News from Miriam Sebaggala in Uganda’, The Woman Engineer (Autumn 1970 10:18, p. 8)

[11] The Woman Engineer (Winter 1970 10:19, p. 18)

[12] The Woman Engineer (Autumn 1971 11:2, p. 12)

[13] The Woman Engineer (Spring 1972 11:4, p. 14)

[14] The Woman Engineer (Summer Autumn 1974 11:13, p. 15)

[15] The Woman Engineer (Spring 1975 11:15, p. 14)