By Emily Rees

It has been a strange perversion of women’s sphere […] to make them work at producing the implements of war and destruction and to deny them the privilege of fashioning the munitions of peace.

Katharine Parsons (Magnificent Women, quoted on pp 12-13, Kindle edition)

The above quotation, spoken by Katharine Parsons, wife of renowned engineer Sir Charles Parsons, in 1919 at a Victory meeting in Newcastle upon Tyne, captures the sentiment that led to the founding of the Women’s Engineering Society (WES) on 23rd June 1919. After spending the war working in factories and industry, women were facing being sent home from these jobs, due to the Restoration of Pre-war practices Act (1919), which made it illegal to continue hiring women in roles that were previously men-only.

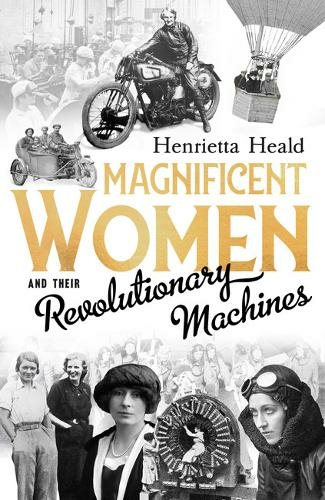

In Henrietta Heald’s book Magnificent Women and their Revolutionary Machines (Unbound, 2019) both the frustration and the hope that came with the end of the First World War are captured and we see how this propelled WES into being. Spearheaded by Katharine Parsons and her daughter Rachel and joined by women who had already made careers for themselves in the broader field of engineering – including housebuilder and suffragette Laura Annie Willson and automotive engineer Margaret Rowbotham – the society sought to defend the place of women in engineering.

Heald provides an evocative account of the meeting where the seven founders came together in London, giving details of the different women’s lives and their routes into engineering. In coming together, they created a society that still survives to this day, with the same mission to support women in finding a career in engineering.

In the subsequent chapters, stories of the remarkable achievement of the members of WES are shared, from the various patents held by mechanical engineer Verena Holmes, to the remarkable work of aeronautical engineer Beatrice Shilling during the Second World War.

Archival material is used to great effect, in particular from the WES archives held at the Institution of Engineering and Technology, giving voices to these women. Often the playful, familiar way the women spoke and wrote to each other comes to the fore, such as when Margaret Partridge asks Caroline Haslett in a letter from 1925 ‘am I a Lady or an engineer – what are you?’ (quoted on p. 130, Kindle edition).

Magnificent Women sets out, however, to focus primarily on just two women: founder and first President, Rachel Parsons and the first appointed secretary, Caroline Haslett. Both, Heald claims, have been largely forgotten by history, despite their contributions.

Though they both ended up as key proponents of WES, the divergent nature of their upbringings is emphasised. Rachel, as the daughter of Sir Charles Parsons and Katharine Parsons, grew up in aristocratic privilege. The exploration of the legacy of women as technical thinkers in the Parsons lineage is brought to the fore, showing why Rachel’s desire to study mechanical sciences at Cambridge was perhaps not so inexplicable (alongside growing up watching her father working on his inventions).

Caroline, on the other hand, grew up in humble surroundings, but, similar to Rachel, she too gained an early interest in engineering through family. Heald’s research reveals that Caroline also took an interest in her father’s work (he was a railway signal engineer), which may have precipitated her interest in engineering, before joining the Cochran boiler company.

Father and daughter relationships do seem to be of great importance as a route into engineering before World War One, as other examples, such as Henrietta Vansittart, Blanche Thornycroft and Dorothée Pullinger also show. There might have been more some more detailed analysis in the book about the larger picture of how women before the First World War came to be interested in engineering, in addition to the story of the Parsons family.

Magnificent Women does manage to survey the sheer amount of activity taking place in engineering by women in the early 20th century, creating a striking sense of the momentum of change for women at this time. The full scope of this is explored in another recent book, Ladies Can’t Climb Ladders: The Pioneering Adventures of the First Professional Women by Jane Robinson (Doubleday, 2020), where the strides forward made by women in engineering are explored alongside entries into other professions, such as law, academia and architecture.

Educational opportunities are greatly important for progression and Heald includes illuminating descriptions of women’s experiences as students of engineering and other related subjects, such as maths and physics. The University of Cambridge is focused on, where many women studied, including Rachel Parsons, despite it not awarding degrees until 1948. The early cohort of women engineers at Loughborough College in 1919, which included Claudia Parsons and Verena Holmes, is recounted, highlighting this as a key educational institution for supporting women in taking engineering degrees.

When reading Magnificent Women, one might question the continued focus on the Parsons women, as both eventually withdraw from WES, as explored in the book. There is perhaps some digression away from engineering and inventing in the exploration of Rachel Parsons’ tragic end and it could be argued that Katharine Parsons was the more important of the two in terms of an overall contribution to women’s place in engineering. Interestingly, the emphasis is also put on Rachel, not Katharine, in Women Can’t Climb Ladders.

Certainly, the pivotal role of Caroline Haslett cannot be denied and Heald uses Caroline’s own words to great effect to summarise her world view:

I see in this new world a great opportunity for women to free themselves from the shackles of the past and to enter into a heritage made possible by the gifts of nature which science has opened up to us.

Caroline Haslett (Magnificent Women, quoted on p. 184, Kindle edition)

Success and failure, prejudice and strides forward, mark the early years of WES and the lives of the women who carved careers for themselves in engineering, all of which is evoked in Heald’s rich study. Throughout Magnificent Women, the political nature of the struggle for equality for women as engineers is always at the surface. We may even surmise that the ‘revolutionary machines’ of these women was not so much the inventions (of which there were many) but rather the political tools they wielded to change the expectations about what women could, and would, achieve.