Graeme Gooday (& Emily Rees)

Women were joining the engineering world in increasing numbers from the late 19th century, and especially in the 1920s and 30s. But was this only happening in wealthy older industrial nations in which women had served engineers during the First World War? Not quite!

From the Second World War onwards we see women from all continents taking part, as is evident in the International Conferences for Women Engineers and Scientists that began in the 1960s. In this blogpost we look at some women in Asia and Africa who aspired to a life in engineering.

How do we locate such women’s stories? One place to look is in The Woman Engineer, the journal of the world’s first dedicated society in this area: the UK Women’s Engineering Society (WES), both launched in 1919. Although written from an Anglo-centric viewpoint, its digitally searchable contents allow at least a search for information to identify individuals who can then be researched further by other means in their own countries.

In a previous blog post we looked at the WES membership directory for 1935 and saw how women in the USA and Germany had joined the Society by then. But if we check The Woman Engineer for that year to look beyond WES members, we see the first aspirant engineer from India, and a few years later a female civil engineer from China.

Thanks to the outstanding volunteering work of Electrifying Women partner Nina Baker (whose own blog is available here), we have a list of all women named in the entire run of the Woman Engineer from 1919 to 2014 and her work has enabled us to identify articles on women in Eastern and Southern nations.

First mentioned is the precocious Miss Kamlabai Jog, in a press report from 1935 clearly engendered by her father – hence perhaps the imposed expectation that his daughter should prove herself directly against the physical capacities of her male counterparts:

Miss Kamlabai Jog, aged 15, is the first girl student admitted to a school of engineering in Bombay – possibly in the whole of India; she has joined the wireman’s class at the Victoria Jubilee Technical Institute. According to her father, this is only a preliminary course to test her capacity to stand the strain of physical work; it is his intention that she shall take a course in ground engineering, gliding and aviation, to qualify for an air pilot’s licence. [1]

Although nothing further has yet been traced on ‘Miss Jog’ it is striking how closely her father’s expectations match those of the – by then – world famous Amy Johnson in securing aeronautic qualifications.

Could this be evidence that Johnson’s widely-reported international solo flights, for example from England to Australia in 1930, were inspiring women across the world to emulate her achievements, not least in the (then) British Empire? 1935 was after all the year that Johnson (as ‘Mrs James Mollison’) became President of WES.

A decade later in the summer of 1945 we find the next reference to a female engineer in India: Mrs. Ayyalasomayajula Lalitha, who was a graduate of Madras University, with a Bachelor of Engineering degree with honours. After a year’s practical training in the electrical department of the East Indian Railways, she was by then a technical assistant in the Indian Government’s Office of the Electrical Commissioner.[2]

This news appears to have been readily available to WES since Mrs Lalitha was at that point a student member of the Institution of Electrical Engineers (London). Three years later, she was a full member of WES. In the ‘News of Members’ section of The Woman Engineer for Winter 1948-9, we learn that Lalitha had taken up a new post as a Junior Engineer with Associated Electrical Industries (India), Ltd., at Calcutta.[3]

Twenty years later, Mrs Lalitha was WES’s national representative for India in the organizing the Second International Conference on Women Engineers and Scientists (more on which later).

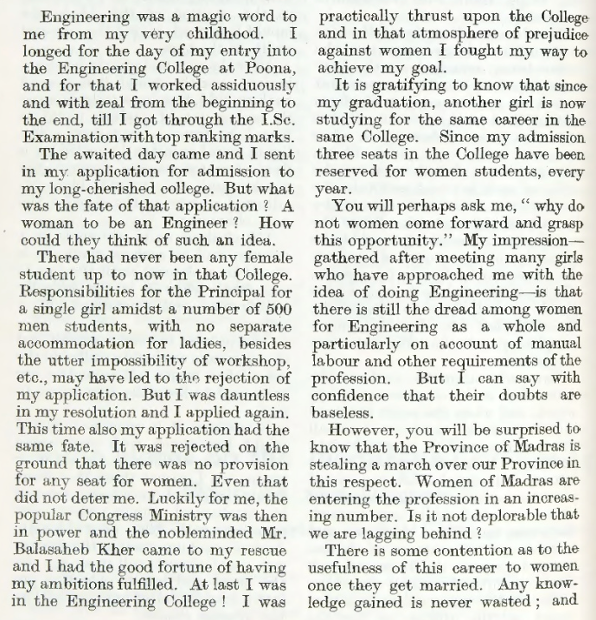

The scope for Indian women to take part in engineering increased considerably as the Empire approached its end after the Second World War. In 1946 the Bombay Presidency Women’s Council organised a Conference on ‘Women in Industries, Trades and Professions’.

The topic of ‘Women in Engineering’ was discussed there by engineering student Usha D. Desai, apparently India’s first trainee civil engineer. Her account was published in the National Council of Women in India Bulletin, and reproduced soon afterwards in The Woman Engineer:

As regards the pressure to pursue a domestic life, Ms Desai argued that an engineering degree was perfectly compatible with marriage. She asked her readers somewhat rhetorically: ‘Don’t you think that a Civil Engineer can be the Domestic Engineer of her own home[?]’

She pointed out that gendered restrictions implicitly operated in expectations about the kinds of civil engineering female practitioners would be expected to undertake: ‘…for a woman Civil Engineer the best opportunities for her lie in the pursuit of Town-planning, Housing and Sanitation.’

So not for her the bridges, railways, roadways or other non-urban constructions that were presumably still the conventional prerogative of the male civil engineer in an impending post-colonial India.

The cultural restrictions wrought by marriage were not universal. If we look at two women from Russia and China who joined WES during the latter years of the Second World War, their marital status as ‘Mrs’ is very clearly flagged.

These two were Mrs Ying Hsi Yuan who held a degree in Civil Engineering awarded by the National University of Peiping [Modern Hebei] and a Mrs E. Peierls who held a BSc Physics, University of Leningrad (also mentioned is new member: Miss S. Constantine, who won a Scholarship for Girls of the British West Indies, and studied chemistry at Birmingham).[4]

In fact, Mrs Yuan was by then a post-graduate student in engineering at Liverpool University, having previously studied civil engineering at Peiping, 1935-39, and practised at the Bridge Design Office in China’s Ministry of Communications, 1939-41.

Newly arrived from China, Mrs Yuan was guest of honour at the WES conference at Mottram Hall, near Macclesfield, Manchester in 1943 – one of the very few such locations not requisitioned for war duties at the time.[5]

The Woman Engineer’s coverage of this conference includes a charmingly cheerful picture of Mrs Yuan poised between Gertrude Entwisle as WES President on the left, and Caroline Haslett on the right (see below).

The rise of women engineers with moves to post-colonial independence are also apparent in the African regions of the former British Empire. News of women engineers from these countries arrived for the first time in the 1960s. And as previously, The Woman Engineer typically reported at first hand on students who travelled to Britain to study.

This is how we learn, for example, of Miss M. Muwanga[6] who travelled to Manchester in 1965 to be a special trainee at Associated Electrical Industries (formerly Metropolitan Vickers) in Manchester, while studying for a H.N.C. at John Dalton College of Technology, Manchester (now Manchester Metropolitan University).[7]

More substantial mentions of African women come with the arrival of the International Conferences for Women Engineers and Scientists. From reports of the first such conference organized by the USA Society of Women Engineers (SWE) in New York in 1964, there is no direct evidence that any participants outside the Europe or the USA were given a platform to speak.

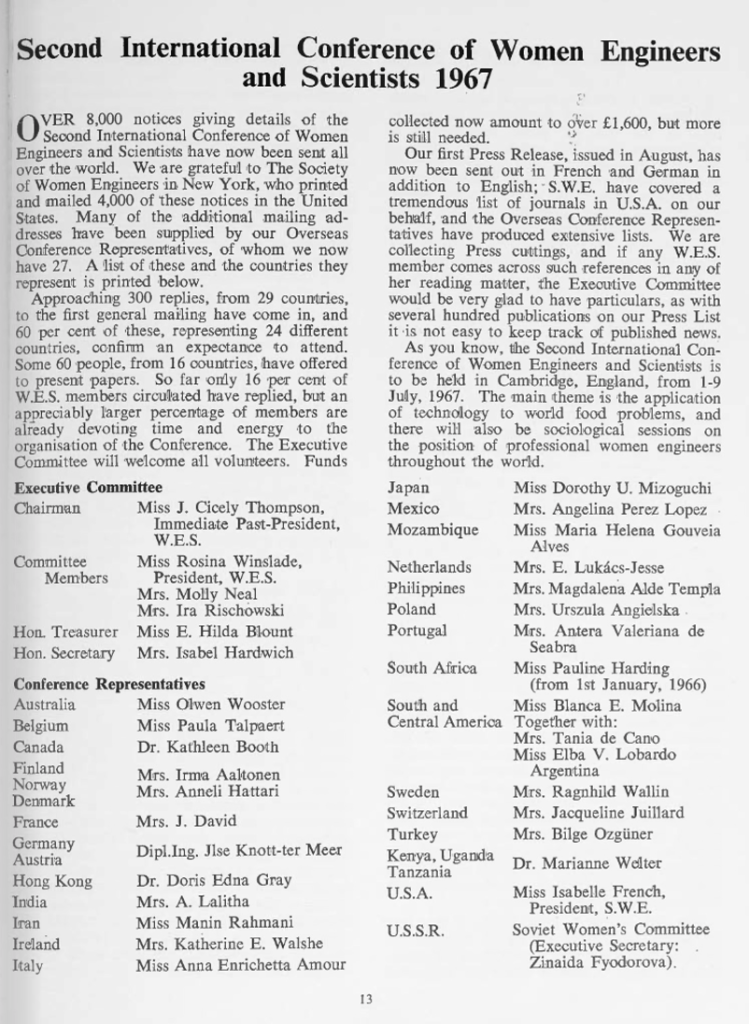

But representatives of many more countries than just Europe and the USA had taken part. As WES was a major co-organiser of the Second international Conference of Women Engineers and Scientists held in Cambridge, England in 1967, The Woman Engineer gives us a detailed analysis of who was already involved in planning the meeting.[8]

We see here that representatives for African nations include Mozambique (still then a Portuguese colony), and four new nations that had recently ceased to be British colonies: Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and South Africa. In Spring 1966, The Woman Engineer announced a plan to add Mrs Ebun Ade-Hall as conference representative for Nigeria.[9]

This 1967 Second international Conference of Women Engineers and Scientists had two distinct themes: the application of technology to solve world food problems, and the sociological question of women’s representation in engineering throughout the world.

In the event, we know that a Ghanaian representative spoke to the first of these wider themes: Letitia E. Obeng gave a paper on ‘Man-made lakes as a source of Freshwater fish production in Africa’. Written by Dr Obeng as Director of a new hydro-biological research institute of the Ghana Academy of Sciences, this piece explains how artificial lakes have the potential to enhance the supply of fish much more effectively than damming rivers to form lakes.[10]

This and many other papers were presented in summary form in The Woman Engineer for autumn 1967. For example, ‘The Position of Women Engineers in India’ was the subject of a paper by K.K. Khubchandani. This revealed that a recent survey identified 275 women in India’s 93,000-strong community engineers, and although female engineers were mostly allocated office work in design, development, teaching and research rather than fieldwork, there was hope that labourers would eventually be persuaded to accept female authority in field projects.[11]

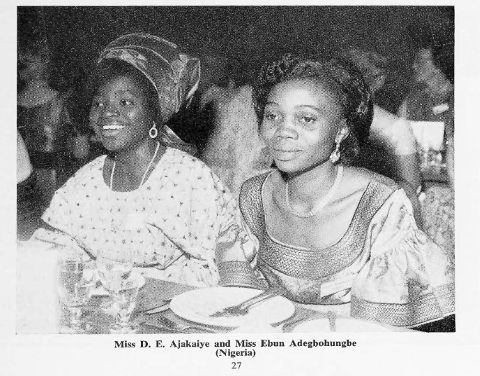

Pictures in The Women Engineer from the conference banquet at Churchill College, Cambridge were particularly striking in revealing the diversity of international attendance, for example, the picture of two conference attendees from Nigeria, Miss D.E Ajakaiyi and Miss Ebun Adegbohungbe (see the very first image above).

Letitia E. Obeng of Ghana was one of several international guests asked to comment, in a two-page article, on this 2nd ICWES Banquet. She observed that this meeting compared well with the inaugural meeting three years earlier in New York, and had a very special purpose in the overall structure of the event:

The Banquet could perhaps be looked on as a half-way function which marked the end of the first section of the programme on technology and its application to the food problems. Perhaps one may indulge in a fancy and interpret the Banquet to signify a physical assertion of the superb ability of women to blend a serious attitude to responsibility with an easy acceptance of social obligations. The change from the serious talks in the Chemistry Laboratory Hall to the gay atmosphere at the pre-banquet reception was a vivid demonstration of the adaptability of the human female to varying conditions.[12]

This combination of conviviality and serious purpose in uniting women around the world to harmonize engineering with human flourishing continued at the ICWES meetings that have taken place every 4-5 years since. As we can see from the ICWES archives sources[13] these meetings went to Bombay, India in 1984; to Abidjan, Ivory Coast in 1991; to Chiba, Japan in 2002 and to Seoul, Korea in 2008.

Much more research needs to be done, but we can see how various organisations, including WES and the SWE, provided opportunities for women engineers in many countries to share their view in these international settings.

[1] The Woman Engineer, vol. 4, part 3, 1935, p.34.

[2] The Woman Engineer, Summer, vol. 6, part 3, 1945, p.38.

[3] The Woman Engineer, Winter, vol. 6, part 14, 1948-9, p.247.

[4] The Woman Engineer, Vol. 5, part 19, 1944, p.305.

[5] The Woman Engineer, Winter Vol.5, issue 17, 1943, p.285.

[6] Nina Baker suggests she might be from Uganda

[7] The Woman Engineer, Winter, vol. 9, issue 19, 1965, p.18.

[8] The Woman Engineer, Spring, no. 20, 1966, p.3.

[9] Ibid.

[10] The Women Engineer, vol 10, Issue 6, 1967, p.17.

[11] Ibid, p.31.

[12] Ibid, p.24.

[13] Material from the Honorary Secretary at ICWES 1967, Elizabeth Laverick, is available at the IET Archives, Ref UK0108 NAEST 132