by Graeme Gooday

How did one of Germany’s very first female engineers end up working in Britain during World War Two? The little-known story of Ira Rischowski is certainly not one of espionage. Hers is instead a drama of escape from Nazi persecution and narrowing opportunities until she was able to join the UK’s Women’s Engineering Society (WES).

Our previous blog post showed that by 1935 WES attracted members outside Britain, and in fact from several continents. Ira Rischowski’s case shows how a talented migrant could swiftly rise to a position of eminence on WES’s Council. Her personal papers at the LSE Women’s Library and in the Imperial War Museum’s (IWM) oral history collection give us an opportunity to reconstruct some aspects of her extraordinary life.

Unlike in Britain, an aspiring engineer in early twentieth-century Germany needed formal qualifications to enter the profession, and by then many technical universities accepted women to study engineering. In 1919, after six months’ experience in a repair shop for agricultural equipment (arranged through her father’s industrial connections), Ira Rischowski enrolled as the first ever female engineering student at the Technical University in Darmstadt.

The chaotic situation in Germany after World War One created major employment challenges for the first women to qualify as engineers. One exception was Melitta Schiller, an aeronautical engineer who graduated from the Technical University of Munich in 1927. She secured prestigious work as an experimental aviation researcher until Nazi officials learned of her grandfather’s Jewish heritage. Later Schiller served in wartime as a Luftwaffe test pilot.

In 1928, after further workshop training at the electrical company Siemens-Schuckert, the newly- qualified Ira Rischowski found employment. Two years later she became a member of Germany’s central engineering institution: the Verein Deutscher Ingenieure (VDI).

By 1933 there were as many as 618 female mechanics and engineers registered in Germany, and accordingly the VDI set up its own special women’s section. But Rischowski refused to join this women’s group since the VDI had by then become completely Nazified.

Soon her own Jewish parentage and socialist politics became the cause of persecution by the Nazi regime. So Rischowski moved with her family to Czechoslovakia. Yet even in Prague, conditions were difficult so in 1936 she escaped to the UK under the only visa scheme permitted to her: to work as a domestic servant.

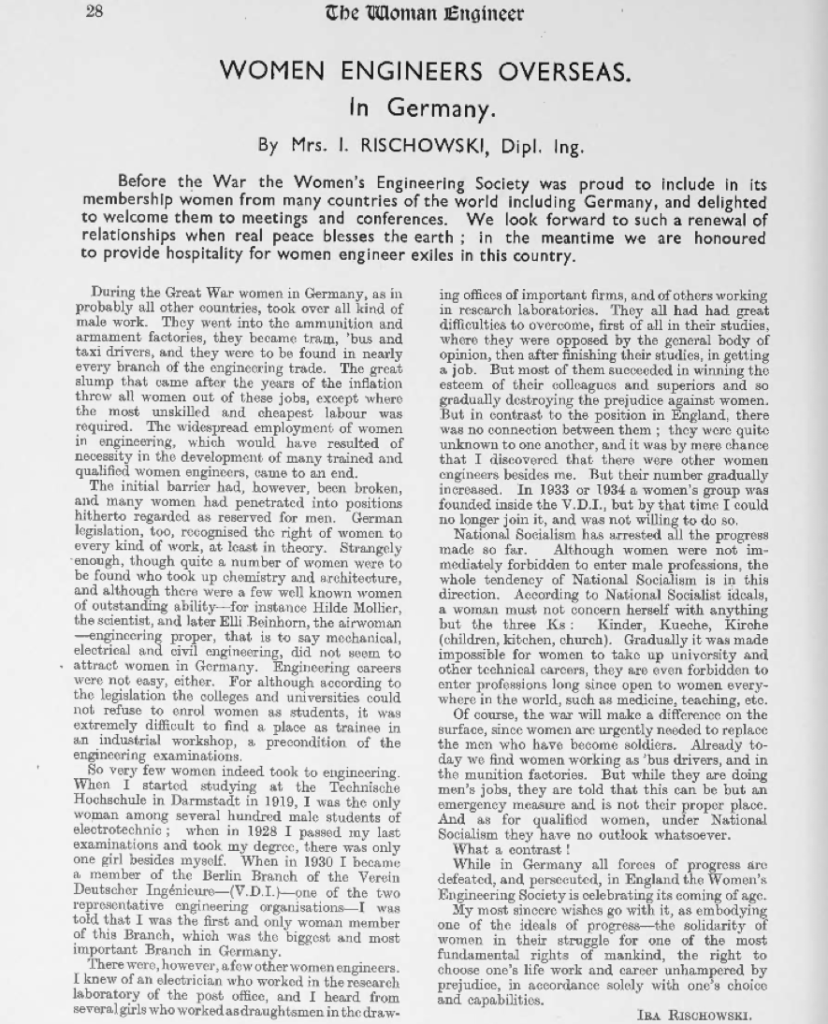

While working unhappily in various menial roles, Rischowski was invited by Caroline Haslett to attend some meetings of WES, and she became an Associate Member of WES in November 1939. For WES’s 21st anniversary, she wrote a piece on Women Engineers in Germany for the WES house journal The Woman Engineer.

When World War Two broke out in September that year, as a German citizen, Rischowski’s position once again became precarious. Deemed to be an enemy alien after an unfortunate misunderstanding with the UK’s Home Office, she spent a year in the Rushen internment camp for women on the Isle of Man. Resilient as ever, she flourished in such adversity, leading many activities, but was yet again denied opportunities to practise engineering.

Once returned to civilian life in 1942, she worked for two years as a draughtswoman and planning engineer at Tuvox Ltd., Middlesex, Rischowski was also then invited to write another piece for The Woman Engineer on women in German engineering before the War. While cherishing Germany’s willingness to welcome women into technical careers on a greater scale than in interwar Britain, she lamented the reversal of this liberal German trend under the reactionary Nazi ideology that recast women’s place to be ‘in the home’. As a naturalized refugee from Germany, Rischowski sharply denounced all aspects of Nazism.

After the War, Rischowski’s position in the UK Women’s Engineering Society advanced in 1948-9 to full membership and service on its Council until 1977. Her meticulously preserved records of WES Council meetings show that Rischowski keenly supported efforts to open up British women’s horizons to engineering. For example, she kept very full notes of a WES-sponsored conference for school teachers on ‘Careers for Girls in Engineering’ in July 1957.

Latterly Rischowski took part in numerous gatherings for women eminent in science and engineering in both Europe and the Americas, notably the International Conference of Women Engineers and Scientists (ICWES) that met every three-four years from 1964. These were initiated by the US-based Society of Women Engineers (SWE), and Rischowski herself worked closely with them to organize the second ICWES gathering at Cambridge in 1967.

Intriguingly in the Proceedings of the first ICWES she is listed as ‘Mrs. Ira. Rischowski, Dipl. Ing., VDI, Elliott Process Automation Ltd. (Elliott Bros. Ltd.) London.’ Neither standard histories of electronics nor of the Elliott companies in particular record her contributions to computing. Indeed information from the LSE library indicates only that from 1944 Rischowski worked as draughtswoman for James Gordon Ltd in London and then Head of the Projects Department from 1956 until retirement. Is there perhaps a mystery here…?

Suffice to say that details of Ira Rischowski’s actual work in engineering are scant; without such information it might be a challenge to memorialize Ira Rischowski in Wikipedia as an engineer, per se. Nevetheless, upon her death in 1989, the WES President Dorothy Hatfield recalled with admiration Ira Rischowski’s work as a major ICWES organizer and indeed that for WES itself she had been ‘an inspiration to us all’.