by Emily Rees

Tracing the history of women in engineering can be challenging; often women’s work is undocumented or disguised. As Elizabeth Bruton’s previous blog post discussed, material held in archives such as the Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET) is invaluable to researching the long history of women in engineering.

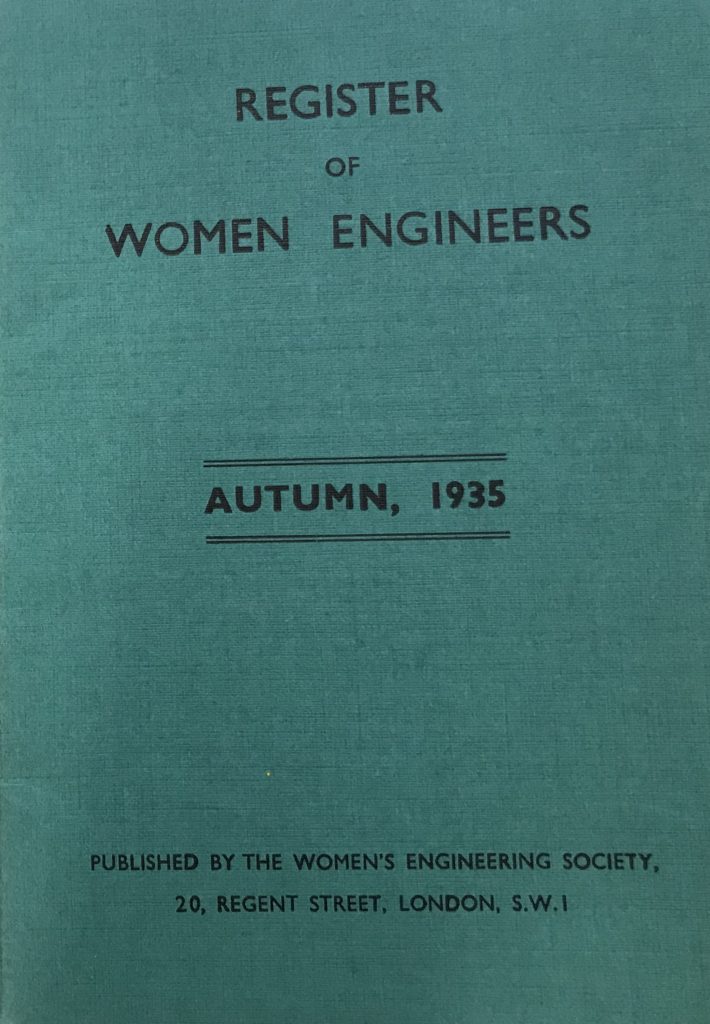

In this blog, I will focus on a small, but incredible revealing, source from the IET archives: the Women’s Engineering Society (WES) Register of Women Engineers, published in the Autumn of 1935.

Though the foreword to the register recognises the incompleteness of the record, it is an important resource for researching the careers of women in engineering in the interwar period. Interestingly, this was not a regular WES publication and we aren’t entirely sure why it was produced in 1935.

At first glance the booklet appears as merely a register, listing names, qualifications, place of work, hobbies and contact details, but if we look more closely at the information the women provide, we can learn large amounts about the various pathways that women took in the early twentieth century and the wide-ranging careers they had in the field of engineering. What’s more, we get a small glimpse into the personalities and passions of these women, providing us with a sense of who these women were and what engineering meant to them.

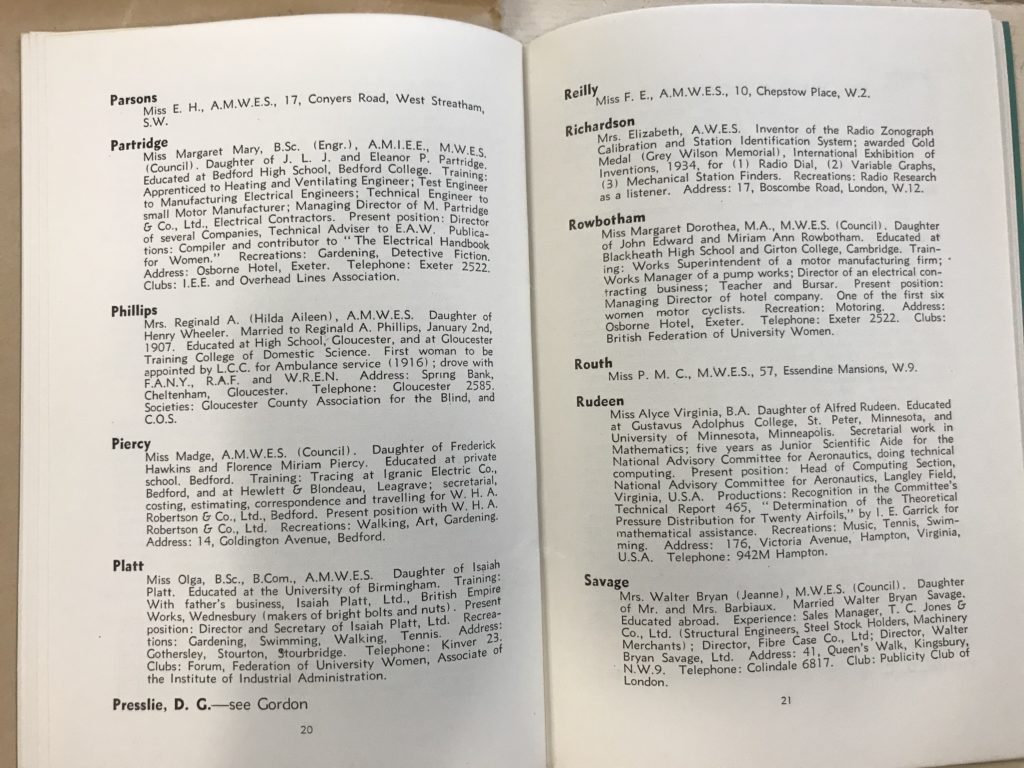

On the subject of education, the register brings to light the different ways in which the women entered into engineering-related jobs. Some of the women have bachelor’s degrees (though not all of these are in engineering) and a few entries list postgraduate qualifications, including a PhD holder. The universities listed include UCL, Cambridge and Birmingham, while for entries from women who qualified in the United States, Columbia is listed more than once, as is the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

The register shows that a more common route into engineering-based professions was through attending college. Several entries mention college courses of some kind, including evening courses and correspondence ones. Both the College of Technology in Manchester and the Royal Technical College in Glasgow appear in more than one entry.

These more ‘formal’ routes are by no means the only ways in which the women in the register made their way into engineering, other entries speak of teaching qualifications in related subjects, while several women, who mostly left formal education after school, describe their education in terms of apprenticeships or learning on the job. A few entries make reference to war-time work such as working in factories or driving ambulances as part of their formative educational experiences.

These varied pathways into engineering help us to see that there were different opportunities for women to access education and training, whether through more traditional academic routes, or more practice-based methods, which may have allowed a range of women, from various backgrounds, to find work in the field.

We find something similar when we look at the variety of work experience and roles that are listed in the entries. If the women’s educations were a smorgasbord of pathways, the various roles they filled is no different: there are reports of work as teachers, draughtsman, researchers, assistants, secretaries, consultants, and writers. Again, we find certain locations reoccurring, especially where there were companies that we know hired large amounts of women, such as Ferranti in Manchester and Galloway in Kirkcudbright.

Through this we also discover the wide range of engineering areas that the women were specializing in, there are references to women working in electrical, aeronautical, chemical, mechanical, naval and metallurgical engineering. Women’s work in engineering was not concentrated in any one specialty or job type; they were working across fields, with varied educational backgrounds, in a range of roles.

Furthermore, the nationalities and places of work of the women is another factor with large variables. Not only are there examples from across the United Kingdom, there are several entries from the United States, including Lillian Gilbreth, who famously fought for the improvement of women’s domestic lives using her training in psychology and domestic sciences.

There are two entries from women educated and working in Germany and one in Australia. Under the contact details, we find that some of the women, though educated in Britain, live as far afield as Palestine, Egypt, and New Zealand. It reminds us that WES’s membership was truly international, due to it being the first engineering society for women in the world.

Beyond their working lives, we are given a small insight into the women’s leisure pursuits, as their hobbies and interests are listed. The women’s interest in engineering often spills over into their private time. A more eccentric answer comes from a Mrs Cecil Roland McKenzie who states her hobbies as: radio experiments, microscopical work, and tropical fish hatchery. More frequently, driving or motoring appears in the list, with flying coming up a few times.

A common theme across the leisure pursuits is the abundance of outdoor, energetic activities, including sailing, skiing, team sports, riding and, for a few, fishing and hunting. Going against the stereotypical image of the domesticated housewife, the list suggests a group of women living fast-paced dynamic lives, beyond the confines of domestic drudgery (which leading WES member Caroline Haslett was so keen to relieve women from).

Though, on the surface level, only a functional document, the register gives us an indication of the professional pride that these women took in their work, which is evident in the way they share their professional achievements, including patents, memberships, and writing. To cite only two, Margaret Rowbotham (one of WES’s founding members) states that she was one of the first six women motorcyclists and Mary Miller writes that she was came sixth in a class of fifty in Advanced Mechanics and that she was ‘the only girl.’ These examples show women who are proud to have been pioneering in some way and to have broken through barriers.

There are too many achievements to list here, but reading the entries highlights the vast range of activities these women had done, from the technical to the literary, and, in this way, the register acts not just as a directory of women in engineering but as a celebration of them too. In more practical terms, it allows us to see which WES members were practising engineers and those which were involved with engineering in more peripheral ways, but still found a home within WES.

If you are interested in exploring the stories of women in engineering in a creative fashion, we will be holding creative writing workshops, the first of which will be at Armley Mills Industrial Museum in Leeds on the 15th September, book here.