By Helen Close, WES Centenary Trail Project Officer, with Graeme Gooday & Emily Rees of the Electrifying Women project

I can’t understand your horribly humible [sic] attitude of mind towards Claudia [Parsons] and myself. You are just as clever as we are, only you are married and no longer required to make an active use of your brains![1]

So wrote Verena Holmes, the 33-year old recent Loughborough College engineering graduate, in 1922 to her friend Nancy Johnson, an automobile laboratory assistant at that college. Verena was not only a great inspiration to her fellow engineers but clearly also supportive of women’s opportunities in other domains. Such are the rich and evocative details of Verena’s personal life starting to emerge from letters recently transcribed by Helen Close, and from newly discovered diaries of Verena’s life.

Before these new materials emerged, we already had an impressive picture of Verena as a phenomenally active and creative mechanical engineer, indeed arguably the first woman in Britain to have a full career as a professional mechanical engineer. She not only invented and patented gadgets for both hospitals and railways,[2] but was a highly dedicated member of the Women’s Engineering Society (WES) for her entire professional life.

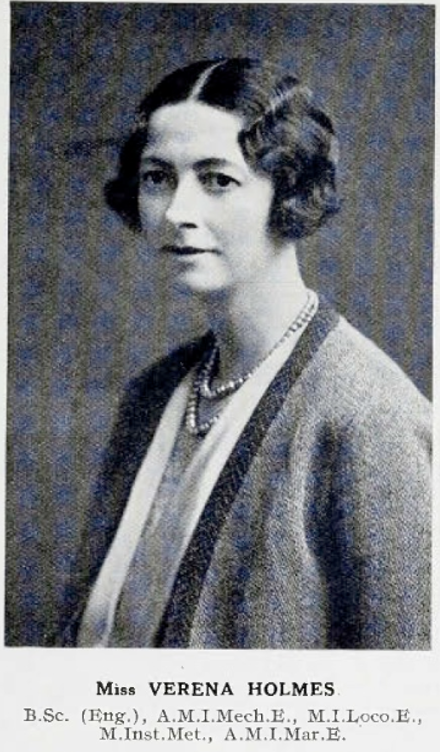

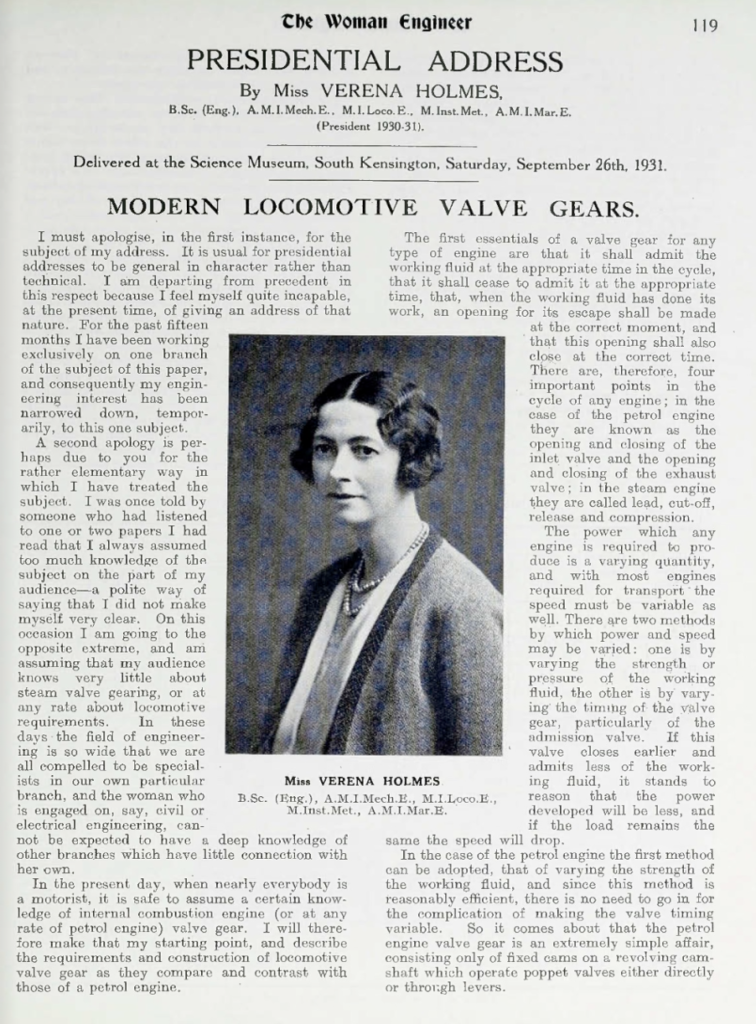

By charming coincidence WES was founded on 23rd June 1919 exactly thirty years after Verena’s own birth. And a decade into WES’s existence Verena was the first professional female engineer to be its President (1930-31), and in fact the first WES President to be elected by its membership. The picture above of Verena as WES President was published by the WES house journal, The Woman Engineer, in September 1931 along with her Presidential Lecture ‘Modern Locomotive Valve Gears’ (see below).

In addition to her professional qualification, we see clearly listed there her membership of institutions of locomotive, mechanical, and marine engineering – this would have been an astonishing range of expertise and institutional recognition for any engineer of her generation.

The poised figure of Verena Holmes (pictured above), wearing elegant suit jacket and necklace, gently staring out from the pages of The Woman Engineer, is one of only a few pictures of her that survive. For other leading figures from WES in this period, there are far more photographic portraits available, so it does beg the question of why there are so few surviving of Verena, especially when she secured an extraordinary number of patents for inventions across a remarkably wide range of inventions in the 1920s and 1930s.

We might speculate that she was not interested in publicity images of herself, instead focusing on producing her incredible output. And as she surely would have wished, her long and remarkable list of achievements shine from the recently updated Wikipedia entry where she is categorised as “an English mechanical engineer and multi-field inventor.”

But who was Verena Holmes? During its centenary year of 2019, the Women’s Engineering Society, was extremely fortunate to receive an email from Nancy Johnson’s grandson. He had discovered fifteen of Verena’s diaries and letters sent to his grandmother amongst his family’s papers.

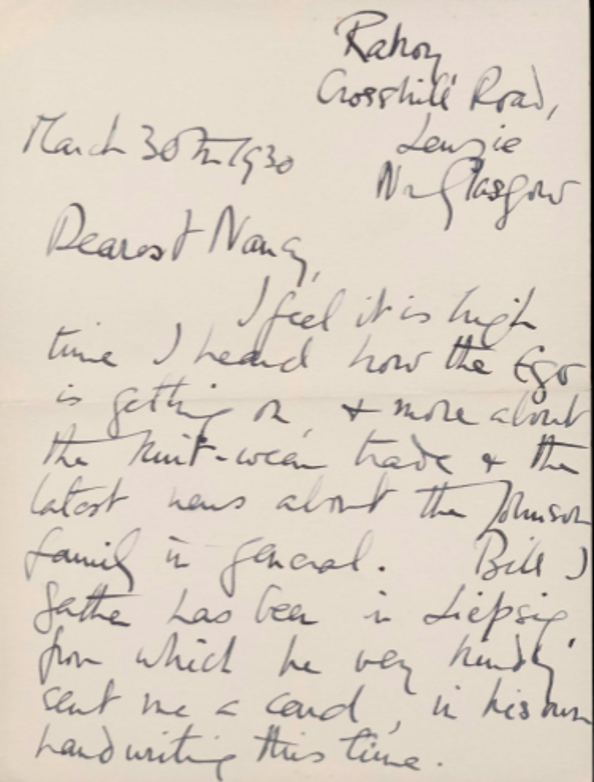

This collection includes seven letters dating from 1922 to 1930, one of which is quoted above. These letters reveal Verena’s fascination with engineering, her quest for recognition of her inventions in a world dominated by men, and her relationship with her father and her sister. More than that, she shows interest in her godchildren’s welfare and an intrigue with others’ sexual relationships.[3]

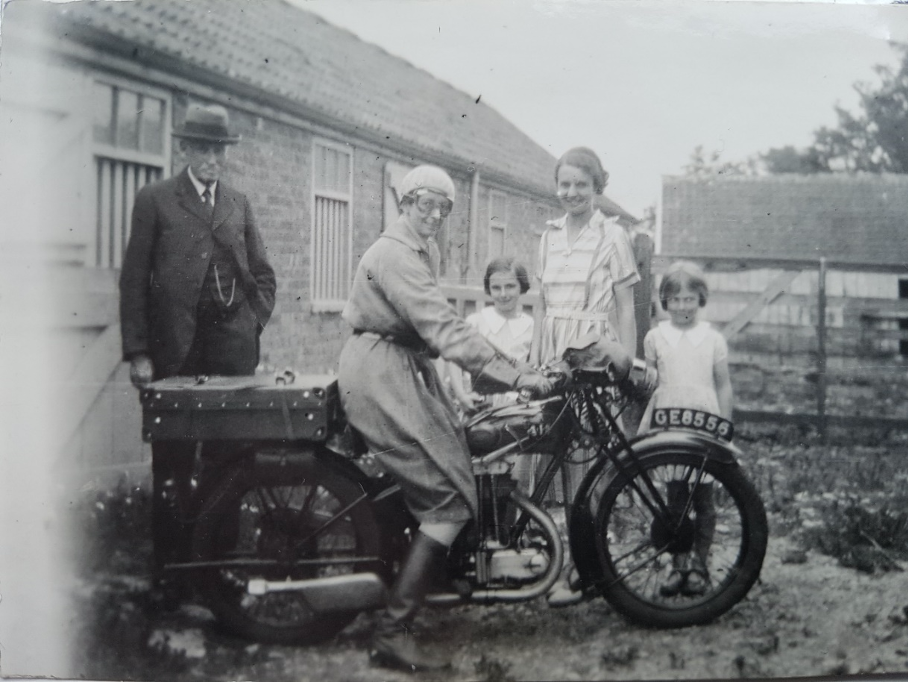

Elsewhere in these letters Verena talks of her adventures with her various motor bicycles: she befriends a local lad of about 15 years and they spend a “most enjoyable afternoon” pushing her motorcycle up hills and down again to get it started.[4]

In her letter of Nov 22nd 1922 to Nancy Johnson mentioned above, she shows concern for her friend’s lack of confidence and asks her to think on what friendship is about:

The best thing about friends is, I think, that one can relapse with them into a state of pleasant imbecility, or at any rate say what comes into one’s head without first bothering to think whether it is clever, dull or idiotic. What do you think about this theory?[5]

A letter sent by Verena to Nancy on 19th July 1925 immediately after the very first International Conference of Women in Science, Industry and Commerce at Wembley is a perhaps the most fascinating of this collection.

Verena recounts the opening of the Conference with Nancy, Lady Astor (Britain’s first sitting female MP), who seemed to make blunders throughout the proceedings: “Lady Astor was a delightful chairman and made the thing go with a swing – She kept doing the wrong thing – such as making her speech before the Duchess of York had declared the Conference open” and indeed before the Duchess of York had made her own formal debut speech. Even so, Verena writes of her envy of these high-born women’s ability to speak in public with wit and ease.

Her letter then goes on to talk about the resignation of WES’s co-founder and sponsor Lady Katharine Parsons at the Extraordinary General Meeting of WES that immediately followed the Conference. Her resignation arose from a political division that arose between Lady Parsons and the WES membership over the Society’s future control and direction:

She herself [Lady Parsons] showed the cloven hoof so plainly and gave herself away so painfully, that from wishing to make peace and pour oil on the troubled waters I veered round to feeling that we should know no peace till we are quit of her. The opinion of an American girl who was present was “I’m outside all this and I know nothing about it, but it strikes me she’s just a spoilt child![6]

The collection of letters sent to Nancy by Verena has provided a colourful and often delightful insight into her life. And with the digitisation of both these and her diaries (soon to be transcribed), we are sure that there will be many more such insights to come.

To conclude here is the first page Verena’s Presidential Address from The Woman Engineer vol.3, 1931, showing her writing much more formally to demonstrate her specialist expertise in locomotive technology. The complete version of her address she delivered at the Science Museum in London on 26th September that year be accessed here in a digitised version of that volume of The Woman Engineer.

[1] Verena Holmes letter to Nancy Johnson, Nov 22nd 1922

[2] Henrietta Heald, Magnificent Women and their Revolutionary Machines, Unbound Press, 2019, 98.

[3] In several letters Holmes talks about “Bliss”, presumably referring to sexual intercourse, and is intrigued with a nanny’s illegitimate pregnancy.

[4] Letter dated 30th March 1930

[5] Letter dated Nov 22nd 1922

[6] Letter dated 19th July 1925. For the full story of Lady Parsons’ withdrawal from WES see Henrietta Heald, Magnificent Women and their Revolutionary Machines, 131-133.