By Animesh Chatterjee

Since her pioneering and courageous international solo flight from England to Australia in 1930, Amy Johnson has inspired several writers and engineers. From contemporary news reports to her fictionalised portrayals in a Doctor Who Magazine comic story in 2013, or even piquing the interests of participants in Electrifying Women’s creative writing workshop in September 2019, Johnson and her achievements have been interpreted in different ways.

While Johnson was, and has been, celebrated in more ways than one — from science fiction to feminist comparisons between historical and contemporary experiences of women — in a previous Electrifying Women blog post, we also learnt that Amy Johnson could well have inspired women in Asia and Africa to join the engineering world.

One of the stories that caught my attention was that of Miss Kamlabai Jog who, at 15 years of age in 1935, was the first woman to be admitted to a school of engineering in Bombay, and possibly all of India. We learnt that Miss Jog’s admission to the Victoria Jubilee Technical Institute was a result of her father’s expectations that his daughter would in future “take a course in ground engineering, gliding and aviation, to qualify for an air pilot’s licence”.[1]

While the archives are silent on Miss Jog’s later career, her story, however, raises a broader question in the previous blogpost. Were Miss Jog and her father, among many people across the British Empire, influenced by Amy Johnson’s widely-reported international solo flight and sought to emulate her achievements through a career in engineering and aviation?

In looking to further uncover how Amy Johnson’s achievements inspired women from Asia and Africa to emulate her achievements and build a career in engineering, I began scrolling through the archives. From my initial research into mentions of Amy Johnson in obscure archival materials written in the context of the British empire in India it quickly became apparent that contemporary authors presented some very diverse and interesting interpretations of Johnson’s achievements, skills and technical expertise.

In this blog post, I present some of the findings from a preliminary perusal of the archives. Here, I will reveal how authors interpret Johnson’s achievements as (1) a symbol of Western domination; (2) a symbol of women’s education and cultural progress; and (3) against what patriarchal writers believed were the natural way of things. As we will see, stories of women engineers — even those of the daring and precocious Amy Johnson — are bound within the societies of their time.

A symbol of Western domination

In an edited volume published in 1947, simply titled The British Empire, the civil servant W. J. Grant cited Amy Johnson’s flight from England to Australia as a victory of “skill and technical equipment” over what he believed were the tough climatic conditions of India. Grant believed that while “the vastness of India” meant that the people would benefit from civil aviation, the lack of Indian interest and most importantly, India’s climate, posed two major difficulties to such an enterprise.

Grant wrote: “Some might claim that the climate of India is against a really dependable air transport service. Certainly a monsoon storm is a terrible ordeal for any pilot to face.”[2]

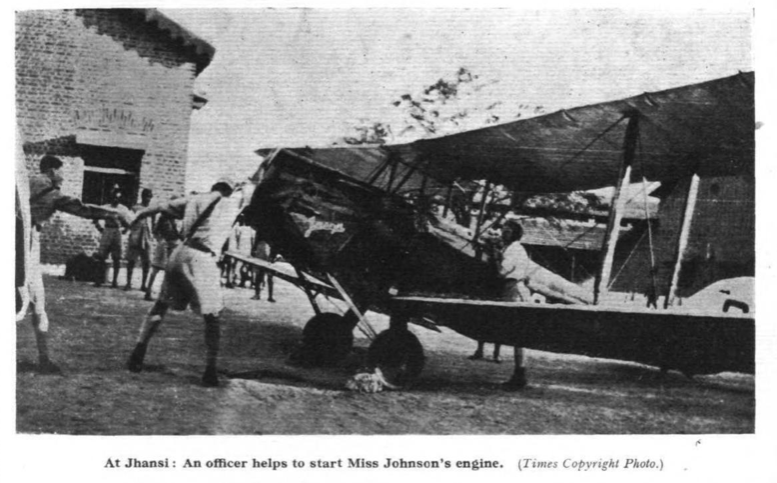

In his discussions of civil aviation in India, Grant also wrote about how Amy Johnson’s stopover in India on her way to Australia showed “that skill technical equipment can be equal to almost anything that the Indian climate can do.”

Grant’s exemplification of Johnson’s aeronautical achievements, however, meant more than a mere account of her skills and technical expertise. He inextricably interwove Johnson’s achievements with the technological modernity from the West.

Such ideas of the conquering of nature in the colonies with technologies and technical skills reflected colonial discourses on how Western science and machinery enabled imperial dominion over the Indian landscape. The rhetoric of the human mastery of nature also reflected those regularly invoked by British scientists, engineers and thinkers in triumphalist narratives of the domination of “natives” who, they believed, viewed nature in mythical and superstitious terms.

A symbol of women’s education and cultural progress

While Grant’s writings invoked Johnson’s achievements as a symbol of Western tools and skills, and their domination of the colonies, Johnson was also referred to by those promoting women’s education in colonial India.

In her book Child Marriage: The Indian Minotaur (1934), Eleanor F. Rathbone — a Member of Parliament for the Combined English Universities — forwarded several ideas on how Indian women’s societies could illustrate to the wider public the evils of child marriage and the benefits of educating women. Rathbone suggested that women’s societies needed to do more than organise the occasional conference and, instead, should look to organise demonstrations, processions and pilgrimages through villages, “preaching their gospel through speech and song and drama and cinema film.”[3]

Rathbone also imagined how an “Indian Amy Johnson” could volunteer to fly over the less accessible areas of India and scatter flyers or write slogans in the sky. Here, Rathbone’s idea of Johnson — or even an “Indian Amy Johnson” — as both a symbol and preacher of women’s education and emancipation mirrored the discursive constructs of the imperial civilising mission, principally envisioned as introducing rationality, and political and cultural progress into the colonies.

In her book, Rathbone imagined how an “Indian Amy Johnson” could volunteer to fly over the less accessible areas of India and scatter flyers or write slogans in the sky. Here, Rathbone’s idea of Johnson — or even an “Indian Amy Johnson” — as both a symbol and preacher of women’s education and emancipation mirrored the discursive constructs of the imperial civilising mission, principally envisioned as introducing rationality, and political and cultural progress into the colonies.

Amy Johnson against the “natural order”

While Johnson’s achievements were celebrated overall, she was also the target of religious and traditionalist Indian nationalists who believed in traditional ideas about women’s roles and homemakers and mothers.

In a section on “Female Education” in his 1938 book Rural Bengal (Her Needs and Requirements), H. S. M. Shaque, an Indian civil servant, while accepting all that “great champions” like Madame Curie, Sarojini Naidu, and Amy Johnson had achieved, wrote that these great names were only exceptions to the rule.

Writing from a patriarchal and paternalistic point of view, Shaque argued that while the achievements of such great women proved the importance of education, they were, however, working “against the dictates of nature itself.” For a traditionalist like Shaque, the focus of women’s education had to be in terms of their roles within the household rather than preparing women to step out of the domestic sphere into what he considered was the man’s world.

Shaque wrote:

The fair sex has her own special department to run and an exclusively reserved function to perform in the scheme of nature, the home, the family and the bringing up of the future generation — a function important enough, difficult enough and sacred enough to entitle her to the greatest esteem and respect that man can command. This is what the fair sex should know and should feel proud of. The rest is all rough and inferior. Leave that to the man.[4] [emphasis mine]

Shaque’s views on women, their education and their place in society were not uncommon for colonial Bengal. The domestic sphere, according to religious traditionalists and nationalists in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, was a safe space for women, and a space they were designed by nature to exist in. The outside world, on the other hand, was an unknown and fearful space for the man to deal with and conquer.

Johnson’s achievements, according to Shaque, could therefore be viewed as a result of her “inferiority complex” to what men had achieved in the outside world so far.

Conclusion

In starting to research Amy Johnson and her influence on women engineers in Asia and Africa, I found glimpses of insight into how her widely reported and appreciated achievements were interpreted by writers of the time.

This blog post, in adding detail and texture to a life we already know, however, also raises some interesting questions for further exploration of the lives of women engineers in colonial India.

At a time when the male Indian nationalist resolution into the “home” – the woman’s domain – as separate and distinct from the “world” – the man’s domain – was widely discussed and propagated, how were women’s achievements in the engineering world – considered to be the man’s domain – viewed by different sections of Indian society?

What do contemporary discussions of women’s achievements in engineering and the sciences tell us about a socio-cultural milieu where education and white-collar jobs were highly valued, yet women’s education was a strongly debated matter?

Since social and religious reform in late-nineteenth and early twentieth century India revolved so much around the home and the place of the woman in it, how did women who pursued education and careers that took them away from the domestic confines create and define their public identities beyond the familial?

In what ways did a career in engineering offer a space for the mobilization of the Indian woman, and result in the rearticulation of existing ideas of public and domestic spheres in colonial India?

While answers to these questions and many others will require a deeper dive into yet unexplored archives, such an effort will, nevertheless, have important connotations for our understanding of the history of “Electrifying Women” in colonial India.

About the author

Animesh Chatterjee recently graduated with a PhD from the Leeds Centre for Victorian Studies at Leeds Trinity University. His main research interest centres on social and cultural histories of electric supply and electrical technologies in colonial Calcutta/India.

[1] The Woman Engineer, vol. 4, part 3, 1935, p.34.

[2] W. J. Grant, “India” in Hector Bolitho (ed.), The British Empire (London: B. T. Batsford, Ltd., 1947), pp. 94-11 (p.109).

[3] Eleanor F. Rathbone, Child Marriage: The Indian Minotaur (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1934), p.109.

[4] H. S. M. Shaque, Rural Bengal (Her Needs and Requirements) (Sirajganj, Bengal: The Central Rural Development Council, 1938), p.87.